Ce texte a déjà paru sur le site Fugitive Philosophy. Fleeing the Disciplines

fear of a wet planet (rhythm I)

Drexciya (descending AfroMer)

We should linger here for a long while on rhythm : it is nothing other than the time of time, the vibration of time itself in the stroke of a present that presents it by separating it from itself, freeing it from its simple stanza to make it into scansion (rise, raising of the foot that beats) and cadence (fall, passage into the pause). Thus, rhythm separates the succession of the linearity of the sequence or length of time : it bends time to give it to time itself, and it is in this way that it folds and unfolds a “self.” (Nancy, Listening, 17)

What might philosophy do with rhythm ? There are three cardinal points I can think of in regards to rhythm : (1) the chapter on the Refrain in A Thousand Plateaus ; (2) Lefebvre’s posthumously published work on Rhythmanalysis ; and (3) Nancy’s work on rhythm in Listening. There are, of course, other writings on the topic, but these three examples are cardinal points as they mark out different approaches (mind you, within a late Western philosophy – we’ll get to Afrofuturism). In this post I’ll tackle something of D&G.

For D&G, the rhythm is thought as the refrain (from Proust), and thought in its relation to various scapes (np. 349), by which I mean at the most general level, the relationship of belonging, beginning with the refrain of the songbird that demarcates territory (territorial refrains), to the refrain of the here-and-there, the call and response (milieu refrains), to refrains of the people (folk and popular, but also military and fascistic Volk), to geospheric refrains, or longue durée rhythms of the Earth and Universe that are near imperceptible to human phenomenology (geologic time). In each case, the analysis considers the limits in which the refrain can become coded and/or overcoded (from refrains that free to refrains that enclose, from the rhythm of flight/fight, the popular song that frees the mind, to the military march). Second, the refrain is always thought in reference to a sphere (the territory, the Earth, celestial bodies). The great shift of historical rhythm (which D&G see as a history of perception itself – 347) occurs when the romantic refrain that expresses X, whether that be the subject, people or territory (D&G will call these “natal refrains, refrains of the territory… [and] folk and popular refrains (347)), or likewise, refrains that are call-and-response (“milieu refrains” (347)), are superseded by the ‘cosmic refrain’ that is a ‘material of capture’ (342). In this contemporary and cosmic refrain, the ‘mechanosphere’ of the modern age, ‘the age of the cosmic’ – which is about 1978 or so I guess – “the essential thing is no longer forms and matters, or themes, but forces, densities, intensities” (343). Here the refrain is also played to ulterior themes in D&G’s work, insofar as the refrain becomes material-molecular, rather than expressly temporal. The refrain not surprisingly plays out among D&G’s quasi-dialectic of territorialization, deterritorialization & reterritorialization that also confirms modernist sonic-aesthetics :

It seems that when sound deterritorializes, it becomes more and more refined ; it becomes specialized and autonomous. (347)

Where temporality is mentioned, the refrain is given as its a priori ; “The refrain fabricates time (du temps)” (349). And specifically : “Here, Time is not an a priori form ; rather, the refrain is the a priori form of time, which in each case fabricates different times [temps – meters, tempos]” (349). Which seems to imply that territorial relations are a priori (at least “here”) to temporal.

D&G are perhaps the first thinkers of philosophic desire to link the modern refrain with the synthesizer (343), insofar as the synthesizer is the assemblage – the materiality, though tempting to say the materialization, which would perhaps reveal more of an expressionist characteristic of this thought than this point concerning post-expressionism would strictly admit – of the cosmic’s abstract machine of the refrain. Here, Cage and La Monte Young are mentioned (344), insofar as experimental electronic music is the express vehicle of refrains that trade in densities, forces and affect, by way of the molecularization of sound. This particular, modernist reading of the refrain that favours white experimental electronic music allowed these passages to be sampled as theoretical soundbytes for experimental electronic labels wishing to align their sonic aesthetic and work with D&G’s philosophy. Case in point is the Mille Plateaux record label (1993-2004) which, besides its name (and parent & sub-labels such as Force Inc., Ritornelle, and so on) sampled D&G for its press releases, as well as releasing “In Memoriam Gilles Deleuze,” a compilation album dedicated to Deleuze upon his passing. (See Simon Reynold’s article, ‘low end theory‘, published in WIRE #146, 04/1996). Achim Szepanski, label head of MP, has this interesting quote in the Reynold’s article when discussing the 1991 ‘ardcore techno / breakbeat fad of “squeaky voices” (a trend that annoyed most aesthetes and critics alike) :

Maybe it was just our peculiar warped interpretation, but the sped-up vocals sounded like a serious attempt to deconstruct some of the ideologies of pop music. One dimension to this was using voices like instruments or noise, destroying the pop ideology that says that the voice is the expression of the human subject. (Achim Szepankski, quoted in Reynolds’ “low end theory“)

Electronic sound destroys the representative voice of the subject. The “track” is no song ; it does not speak, signify, nor represent. Ample demonstration and explication of the sonic deconstruction of the subject’s voice is to be found in Kodwo Eshun’s More Brilliant Than The Sun, for example when taking on the “Sampladelia of the Breakbeat,” and in reference to Ultramagnetic MCs, Eshun writes that :

The human organism is flying apart. The Song is in ruins. Sampling has cracked the language into phonemes. It breaks the morpheme into rhythmolecules. (03[025])

Aquanauts / Underground Resistance

Eshun’s relation to D&G is complex, insofar as he utilizes several of their concepts – notable re/de/territorialization – while infusing them with the rhythm – intergalactic, interstellar, Afrofuturist – the refrain denies. The cosmic refrain frees sound from territory by way of sonic molecularization (and the assemblage of the synthesizer), and is exemplified in the beatless, static soundwave compositions of La Monte Young and random chance operations of John Cage. Where is Afrosonic rhythm, rhythm in general circa 1979, say the rhythm of disco, jazz, Sun Ra, Muddy Waters or even The Rolling Stones ? Or again : Kraftwerk ? Aesthetic exemplification aside, the question remains why D&G never discuss rhythm that engages the body – dance music – given their philosophical preoccupation with precisely this point, the materiality and embodiment of perception as “pop philosophy,” or what Eshun aptly sums up when he writes that “Rhythm is a biotechnology” (01[007]). Eshun could be responding to – and characterizing – Deleuze in the following :

Traditionally, the music of the future is always beatless. To be futuristic is to jettison rhythm. The beat is the ballast which prevents escape velocity, which stops music breaking beyond the event horizon. The music of the future is weightless, transcendent, neatly converging with online disembodiment. Holst’s Planet Suite as used in Kubrick’s 2001, Eno’s Apollo soundtrack, Vangelis’ Blade Runner soundtrack : all these are good records – but sonically speaking, they’re as futuristic as the Titanic, nothing but updated examples of an 18th C sublime. (05[067])

To sample once again the Zizek soundbyte that is in the air : “precisely.” And it is again worth noting white futurism’s attachment to celestial bodies in the case of Holst, the geospheric weightdown of weightless music to some kind of terra firma. Everything Eshun will explore insofar as Afrofuturist sonic fiction – the acceleration of rhythm as the biotechnology of the beat – though it can be thought in the matrix of D&G, simply echoes and bleeds beyonds the concept of the refrain, insofar as the refrain remains tied to a territory, and in its molecularization, forgets the body. Interstellar sound can’t be grounded in this fashion though it can be sensed by way of fear, dread, dance, movement, headsonics, and the sonic deterritorialization of the soul-subject-body. Even as the Detroit techno of Underground Resistance proceeds by way of enlarging its territorial communication – Nation 2 Nation, Galaxy 2 Galaxy, Universe 2 Universe, as three 12″s claim their succession in the World Power Alliance – it is by way of exploding the territory with tones. Sun Ra is put to use at 130BPM. And as Eshun notes, rhythmic techno also detonates the representational grounding of hiphop :

UR’s World Power Alliance expands on Public Enemy’s Fear of a Black Planet, replacing planetary nationalism with a sonic globalism. (07[122])

Or to resample by way of “Electronic Secession :”

Techno secedes from the ruthlessly patrolled hoods of Trad HipHop. HipHop updates blaxploitation’s territories ; it represents the street. By opting out of this logic of representation, Techno disappears itself from the street, the ghetto and the hood. Drexicya doesn’t represent Detroit the way Mobb Deep insist they represent Staten Island. (07[102])

Without representation, techno is free to become autonomous to the body itself in its sonic fictions of dance/dreaming and interstellar travel of the intellect via soundwaves. But with this imaginary, the loss of terra firma also means that techno does not represent Detroit, meaning that something of techno’s possible impact to the hierarchy of the popular music industry is lost. Such is the choice taken (though evidently a great influence was felt in the early ’90s worldwide, and remains in Europe, of electron sound ; North America has reterritorialized upon the pop subject’s authenticity, whether by way of hiphop, r’n’b or pop proper, even insofar as this authenticity is the most plastic of fictions, sung & strut).

Techno’s globalism goes underwater with Drexicya (the aquatic AfroMers, descendants of those souls sent overboard during the Middle Passage of the Black Atlantic) and interstellar with X-102 (The Rings of Saturn). The beat syncopation of rhythm adds an element missing to D&G’s static wave-molecular modernism, for

Techno becomes an immersion in insurrection, music to riot with” (07[118]).

The utility of dance music is its ability to form and froth a body, to lather it up into a furious funk, to reconnect the mind to a whirling movement, to the dervish, to becoming-lost as a way to riot.

fear of a wet planet / Underground Resistance

the city be the rhythm invisible (rhythm II)

in the shadows of the urban (I)

Henri Lefebvre’s last work, published posthumously, and intriguing as it is something of a skeletal meditation, is entitled Rhythmanalysis. In it Lefebvre advances two hypotheses, each unique, urgent, and radical in scope. The first, following from The Urban Revolution, is that the engine of history, so to speak, is no longer the economic base, by which Lefebvre upends the Marxian hypothesis that the means of production drive the social production of history and class. Lefebvre instead posits the urban : the urban, in itself, constitutes a breakdown between city and country, between the means of production and the superstructure. The urban is a new, epochal and thus world historical condition – a virtual set of possibilities – encompassing the ‘urban revolution’, which for Lefebvre retains its open, virtual – and thus ateleological – futurity. This thesis, nascent in Lefebvre’s work of the early ’60s (and with the SI), comes into its own in Rhythmanalysis, wherein a second hypothesis takes shape : that the urban can be read, can be analysed, by a kind of phenomenology of rhythm, a phenomenology or psychoanalysis of the urban condition.

Unlike the sociological interpretation of Lefebvre – in which the ‘urban’ is seen as an architectural phenomena of the city’s expanse, of the suburb, and in which Lefebvre’s work is thus dated to the level of a (now dated) sociological fact – I am intrigued by the broader philosophical purchase of Lefebvre’s thought on the urban and rhythmanalysis.

What is particular of this analysis is that it follows from Derrida’s deconstruction of phenomenology (in Speech and Phenomena), insofar as phenomenology cannot effectively bracket the sign by way of its transcendental reduction (the bracketing of the world in the attempt to encounter the consciousness of the phenomena present-to consciousness, aka intentionality). Derrida’s deconstruction does not discredit Husserlian phenomenology. On the contrary, it opens phenomenology to several fruitful themes, not the least the apprehension of the sign (writing-in-general), a more complex understanding of time consciousness, the substrate of technics (np. Bernard Stiegler), and what Lefebvre calls ‘rhythm’, in all of its differentiated phenomena. (In a similar vein, one can read Derrida’s deconstruction of several of the concepts of psychoanalysis — memory, repetition, time, repression, the return, the symbol — as also opening psychoanalysis to these broader themes, in a more radical sense than Freud’s application in texts such as Civilization and its Discontents.

in the shadows of the urban (II)

Rhythm comes to the fore in Lefebvre (and in Derrida). Rhythm, not as a motif or metaphor for the passing of time, nor of history, class, production or place, but as its occurence in-itself. As something of the stuff of things, the warp and woof of what comes to measure and differentiate. And yet something felt : the affect of differentiated repetition, the felt passing and upcoming, structured into the complex semiotics of ritual, calendar, measured time, music and dance. Rhythm : a way in which to grasp, for Lefebvre, the urban revolution, which is the invisible and silent rhythm, the standing-wave or superposition of obverse rhythms so that their overlay becomes imperceptible (a similar hypothesis is to be found in Deleuze and Guattari’s Thousand Plateaus (more on this later) ; rhythmanalysis opens an encounter, perhaps, between D&G and Derrida, for the analysis of the imperceptible suggests an aporia, which lends itself to a quasi-transcendental approach by way of a quasi-Kantian analysis of conditions of possibility).

(Note to self again : ‘revolution’ here is ambiguous, insofar as it loses its Marxian finalism, becomes a general condition, a rhythm which demands its own rhythmanalysis.)

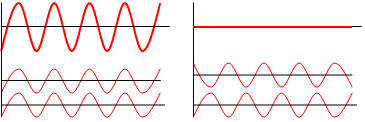

The urban revolution constitutes the dominance of the urban, but in such a way that the urban cannot be distinguished as a rhythm unto itself, but rather as the apparent lack of rhythm onto which differentiated rhythms are perceived. The urban is not a phenomenon to consciousness in this sense ; it is the effect of superposition, in which their inverse relation produces phase cancellation.

Superposition on the right (phase cancellation).

As differences between the means of production and their architectures of habitation and circulation — city and country (and thus their classes, proletariat and bourgeoisie) — merge into a general condition, that of the urban condition, the analysis of rhythmic difference eclipses that of dialectical difference. (At least, this is how Lefebvre sees it ; Derrida would argue that this eclipse is precisely what is at work in-general, though he too, I think, remains deeply ambivalent as to the historical status of différance, and even fundamentally so, insofar as différance must remain indecisive — this at least is how I read the meaning of ‘infinite différance is finite’ in Of Grammatology. In any case, it is this ambivalence that Stiegler exploits as he, unlike Derrida, decisively claims technics, qua the substrate, as the historical condition of the différance of différance.)

Rhythm can be analysed by way of an embodied meditation — a practice in-between phenomenology and psychoanalysis — and, according to Lefebvre, classified into three fundamental categories (arrhythmia, eurhythmia, isorhythmia), and through its analysis the specific characteristics of the urban in its architectural centripetality (the city) can be identified. This process is somewhat flawed, insofar as Lefebvre at times appears to categorize rhythm by way of a dialectic, and to claim that rhythm can identify what would be the essential characteristic — rhythm — of a particular urban locale (city). That rhythm could essentialize a locale, or determine its essential identity, would mean that it entails a dialectical finalism in itself — a hypothesis that strains against Lefebvre’s more radical assertion of the polyrhythmic, and not strictly dialectical, operations of the urban, and of the complexities inherent in the aporia of the urban as the rhythm invisible (obverse superposition : a standing-wave). In this respect too Lefebvre overemphasizes the significance of the city as the site of rhythm, as the privileged place of urban identity. But these are fruitful aporia, by way of a deconstruction, of Lefebvre’s bold meditation on rhythm as an embodied practice (in a way Bataille would appreciate). This embodied practice reveals a way to read a (rhythmic) shift in the technics of world historical conditions (the urban revolution). As any dancer or musician knows (as any body knows), rhythm is felt.

The particular rhythms of a place are observable by way of embodied perception, in the oscillation between stasis (the poses of still meditation, listening, focus) and movement (the dance, the flâneur, the dérive). Radical political practice has taken up the oscillation of rhythm. But this is not the only aspect of rhythmanalysis. Rhythmanalysis affords an opening between différance and embodied experiences of stasis/movement. It generates the context for theoretical dialogue, not the least to continue deconstruction by other means, by way of embodied practice.

Rhythmanalysis, here motivated as an opening to Afrofuturism, to rhythm as practice in which not only the (apparent) dialectic between city/country disintegrates to the general rhythm of the urban, but that between philosophy and practice itself.

in the shadows of the urban (III)