This text was originally published in Michelle Williams and Vishwas Satgar, Marxisms in the 21st. Century, Johannesburg, South Africa, Wits University Press, 2013, p. 34-52. We would like to thank Michael Burawoy for allowing us to publish it on RHUTHMOS.

What should we do with Marxism ? For most the answer is simple. Bury it ! Mainstream social science has long since bid farewell to Marxism. Talcott Parsons (1967 : 135) dismissed Marxism as a theory whose significance was entirely confined to the nineteenth century – a version of nineteenth century utilitarianism of no relevance to the twentieth century. Ironically enough, he penned these reflections in 1968 in the midst of a major revival of Marxist thought across the globe – a revival that rejected Soviet Marxism as a ruling ideology, a revival that reclaimed Marxism’s democratic and prefigurative legacy. The revival did not last long but suffered setbacks as revolutionary hopes were vanquished by repression and dictatorship and then by market fundamentalism. With the final collapse of the Soviet order in 1991, and the simultaneous market transition in China, the gravediggers pronounced Marxism finally dead and bells tolled across the world.

Facing such anti-Marxist euphoria, the last hold-outs often appear dogmatic and anachronistic. Marxists have, indeed, sometimes obliged their enemies by demonstrating their religious fervor in tracts that bear little relation to reality, defending Marxism in its pristine form, revealed in the scriptures of Marx and Engels. The disciples that followed Marx and Engels – Lenin, Plekhanov, Trotsky, Bukharin, Luxemburg, Kautsky, Lukács, Gramsci, Fanon, Amin, Mao – were but a gloss on biblical readings of origins. Today’s epigones do not place Marx and Engels in their context, as fallible beings whose thought reflected the period in which they lived, but as Christ-like figures and thus the source of eternal truth. In their view the founders can speak no falsehood.

Adopting neither burial nor revelation, a third approach to Marxism has been more measured. Many in the social sciences and beyond have appropriated what they consider salvageable, which might include Marxism’s analysis of the creative power of capitalism, the notions of exploitation and class struggle, the idea of primitive accumulation, or even Marxist views of ideology and the state. These neo-Marxists and post-Marxists often combine the ideas of Marx and Marxism with those of other social theorists – Weber, Durkheim, Foucault, Bourdieu, Habermas, Beauvoir, and so on. Indeed, these latter theorists had themselves absorbed many Marxist notions, often without acknowledging their debt, even as they expressed their hostility to Marxism. The neo-Marxists treat Marxism as a supermarket. They take what pleases them and leave behind what does not, sometimes paying their respects at the checkout, sometimes not. They have no qualms about discarding what does not suit the times.

The fourth approach, the one adopted here, is that Marxism is a living tradition that enjoys renewal and reconstruction as the world it describes and seeks to transform undergoes change. After all, at the heart of Marxism is the idea that beliefs – science or ideology – necessarily change with society. Thus, as the world diverges so must Marxism, reflecting diverse social and economic structures and historical legacies. However, Marxism cannot simply mirror the world. It seeks to change the world, but changing such a variegated world requires a variegated theory, a theory that keeps up with the times and accommodates places.

Marxism as an evolving tradition

If Marxism is an evolving tradition, what do all its varieties share that make them part of that tradition ? What makes Marxism Marxism ? What is its abiding core irrespective of the period, irrespective of the national terrain ? What do all branches of Marxism have in common ? If we think of the Marxist tradition as an ever-growing tree, we can ask : What are its roots ? What defines its trunk ? What are it branches ? [1]

The roots themselves grow in a shifting entanglement of four foundational claims : historical materialism as laid out in the Preface to the Critique of Political Economy, the premises of history as found in The German Ideology, notions of human nature as found in the Philosophical Manuscripts, and the relation of theory and practice as found in the Theses on Feuerbach. The trunk of the Marxist tree is the theory of capitalism, presented in the three volumes of Capital, and revised by inheritors over the last century and a half.

Then there are the successive branches of Marxism – German Marxism, Russian-Soviet Marxism, Western Marxism, Third World Marxism – some branches dead, others dying, and yet others flourishing. Each branch springs from its own reconstruction of Marxism, responding to specific historical circumstances. German Marxism responded to the reformist tendencies within the German socialist movement of 1890–1920 as well as capitalism’s capacity to absorb the crises it generates ; Russian Marxism sprang from the dilemmas of the combined and uneven development of capitalism on a world scale, and of the battle over socialism in one country ; Western Marxism was a response to Soviet Marxism, fascism and the failure of revolution in the West ; and Third World Marxism grapples with the dilemmas of underdevelopment as well as colonial and post-colonial struggles.

When we examine this tree we see that Marxism may have begun as a small-scale project that did indeed link people across national boundaries – think of the First International. As classical Marxism garnered popular support it became tied to national politics (Russian, German, French, and so on) from which it expanded into regional blocs – Soviet, Western and Third World Marxism. What is the scale of Marxism today ? Even though its popular base has shrunk, I will argue that Marxism can no longer respond only to local, national or regional issues ; it has to embrace global issues, issues that affect the entire planet. To reconstruct Marxism on a global scale requires, I argue, rethinking the material basis of Marxism through the lens of the market, but not in terms of its geographical scope (since markets have always been global as well as local), nor even in terms of neoliberal ascendancy (since markets have always moved through periods of expansion and contraction) but in terms of the novel modes of commodification.

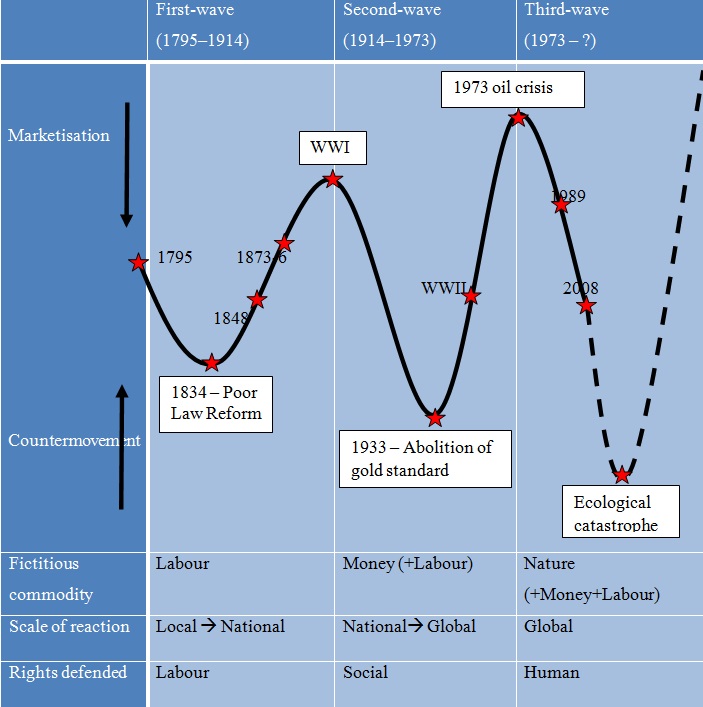

In brief, there have been three waves of marketisation that have swept the world : the first spanning the nineteenth century, the second beginning after World War I, and the third beginning in the mid-1970s. Associated with each wave is the commodification of a leading force of production, successively labour, money and nature. These are Karl Polanyi’s (1944) three fictitious commodities whose commodification, he claimed, destroys their use value. Thus, when labour is subject to unregulated exchange it loses its use value – it cannot be productive ; if money is subject to unregulated exchange the value of money becomes so volatile that businesses go out of business ; and if nature is turned into a commodity it destroys our means of existence – the air we breathe, the water we drink, the land upon which we grow food, the bodies we inhabit. Each wave of commodification spawns a countermovement that is built on a distinctive set of expanding rights (labour, social and human) organised on an ever widening scale : local, national and, presumptively, global. Finally, to each countermovement there corresponds a distinctive configuration of Marxism – classical Marxism based on the projection of an economic utopia ; Soviet, Western, and Third World Marxism based on state regulation ; and finally, sociological Marxism based on an expanding and self-regulating civil society.

{{}}The periodisation of Marxism may be tied to the periodisation of capitalism but the periods themselves are continually reconstructed as a history of the evolving present, a history that makes sense of the present as both distinct from and continuous with the past. Marx (1967) saw only one period of capitalism, Lenin (1963) saw two and Ernest Mandel (1975) saw three. We, too, see three, not based on production but rather on the market as the most salient experience of today. Here I do, indeed, break with the conventional Marxist claim that production provides the foundation of opposition to capitalism. This is no longer tenable in part because production is the locus of the organisation of consent to capitalism and in part because in the face of the global production of surplus labour populations, exploitation is rapidly becoming a sought-after privilege of the few. Exploitation continues to figure centrally in the dynamics of accumulation, but not in the experience of subjugated populations. In the Marxian analysis the experience of the market appears as the ‘fetishism of commodities’, a camouflage for the hidden abode of production, but it is much more than that, shaping multiple dimensions of human existence.

Reconstructing Polanyi

In making the market a fundamental prop of human existence I draw on Karl Polanyi’s theory and history of capitalism. Written in 1944, Karl Polanyi’s The Great Transformation examines the political and social consequences of the rise of the market from the end of the eighteenth century to the Great Depression. The market, Polanyi argues, had such devastating consequences that it generated a countermovement to protect society. The countermovement, however, could be as destructive as the market it sought to contain. Thus it included fascism and Stalinism as well as the New Deal and social democracy. Indeed, Polanyi concluded that such were its consequences that never again would humanity experiment with market fundamentalism. He was wrong – market fundamentalism struck our planet once again in the 1970s, threatening human existence and annihilating communities.

The reason for Polanyi’s false optimism lies in his failure to take the logic of capitalism seriously. While he embraces Marx’s early writings on alienation, he rejects Marx’s theory of history, whether understood as a succession of modes of production, the self-destroying dynamics of capitalist competition, or the intensification of class struggle. But in rejecting the idea of laws of history, Polanyi also jettisons the logic of capital, in particular its recurrent deployment of market fundamentalism as a strategy for overcoming its internal contradictions. This, of course, is where David Harvey (2003, 2005) steps in regarding ‘neoliberalism’ as an ideological offensive of capital against the gains made by labour in the period after World War II. [2]

Recognising the contemporary wave of market fundamentalism leads to questioning Polanyi’s homogenising history of capitalism as a singular wave of marketisation giving way to a singular countermovement – what he calls the ‘great transformation’. Referring specifically to the history of England, Polanyi recounts in detail the way the Speenhamland system protected labour from commodification until the passage of the 1834 New Poor Law that banished outdoor relief. The year 1834 marked, then, the establishment of a pure market in labour that, through the nineteenth century, generated movements against commodification – from the Chartist movement of 1848 that sought to give workers the vote, to the factory movement that sought to limit the length of the working day, to the abolition of the Combination Acts that sought to advance trade unions, to demands for unemployment insurance and minimum wages. These struggles were not about exploitation, argues Polanyi, but about the protection of labour from its commodification. Society was fighting back against the market.

In Polanyi’s history, the commodification of labour was but part of a long ascendancy that continues from the end of the eighteenth century through World War I to the Great Depression. Facilitated by the commodification of money, itself ensured through the regulation of exchange rates by pegging them to the gold standard, the market expanded into the realm of international trade. Opening up an unregulated global market in trade with the fluctuating value of national currencies so destabilised individual national economies that states successively went off the gold standard and undertook protectionist policies. Protectionist regimes took the form of fascism in countries such as Italy, Germany and Austria, took the form of the New Deal in the US, took the form of Stalinism with its collectivisation and central planning in the Soviet Union and took the form of social democracy in Scandinavian countries. In Polanyi’s eye the upward swing in commodification ultimately gives way to a countermovement that could lead to socialism based on the collective self-regulation of society but was just as likely to give way to fascism and the restriction of freedom.

Knowing that Polanyi was wrong about the future, calls into question his account of the past. Thus re-examining Polanyi’s argument reveals that there was not a singular upward trajectory in marketisation but at least three waves of marketisation (see Figure 1). The first takes us from Speenhamland to World War I and is primarily driven by the commodification of labour, followed by its protection, whereas the second wave takes us from World War I to the middle 1970s. The second wave originates with the commodification of money (and a renewed commodification of labour), leading to a countermovement involving the regulation of national economies. The third wave, known to many as neoliberalism, begins in 1973 with the oil crisis and initiates a third wave of marketisation featuring the recommodification of labour and money, but also the commodification of nature. We are still in the midst of the ascendancy of this third wave of marketisation. Along the way we have passed through structural adjustment administered to the failing economies of the South and shock therapy adopted by the post-Soviet regime and its satellites in East and central Europe. Successive economic failures of state-regulated economies served to energise the ascendant belief in the market. The succession of financial crises in Asia and Latin America during the 1990s, culminating in the financial crisis of 2008, served to consolidate the power of finance capital. [3]

What is unique about the third period, however, is the way the expansion of capitalism has given rise to environmental degradation, moving towards ecological catastrophe. Whether we are referring to climate change or the dumping of toxic waste, the privatisation of water, air and land, or the trade in human organs, the commodification of nature is at the heart of capitalism’s impending crisis. The countermovement in the third period will have to limit capitalism’s tendency to destroy the foundations of human existence, calling for the restriction and regulation of markets and a socialisation of the means of production which would be as compatible with the expansion of freedoms as with their contraction.

Figure 1 : Three waves of marketisation

Polanyi’s single great transformation, from ascendant marketisation to countermovement, gives way to three waves of marketisation each with its own real or imagined countermovement. Each wave of marketisation is marked by a leading fictitious commodity. As well as incorporating a new fictitious commodity, each wave of marketisation recommodifies that which had been commodified before, but in new ways. Labour, for example, is commodified, decommodified and then recommodified in successive waves. We should not think of the three waves as compartmentalised and separated from each other, but rather as a form of dialectical progression or, perhaps better, regression.

The rhythm and experience of these waves is different in different parts of the world. Polanyi himself recognises how the first wave of marketisation in the nineteenth century had especially destructive consequences in the colonies where there was, he argues, no capacity to resist the annihilation of indigenous societies. Much as he exaggerated the destruction of the working class in nineteenth-century England, he also exaggerates the destruction of indigenous communities in South Africa. [4] We now know that colonialism actually limited land dispossession, so as to create the basis of indirect rule as well as labour reservoirs for industry. Still, in his exploration of colonialism, Polanyi does raise the question of the differential consequences of marketisation according to position in the world capitalist order.

No less important is the historical context. Thus Russia and China today, emerging from a period of state socialism – itself a reaction to second-wave marketisation – face the simultaneity of all three waves of marketisation, that is, simultaneity in the commodification of land, labour and money. In the Russian case, marketisation, at least for the first seven years of the post-Soviet era, was accompanied by an unprecedented economic decline just as in China it was accompanied by unprecedented economic growth. In Russia, wanton destruction of the party state was inspired by market fundamentalism and the belief in a market road to market capitalism, whereas in China the market was incubated under the direction of the party state. The staggering pace of Chinese economic development is a resounding confirmation of Polanyi’s own argument that markets require political organisation.

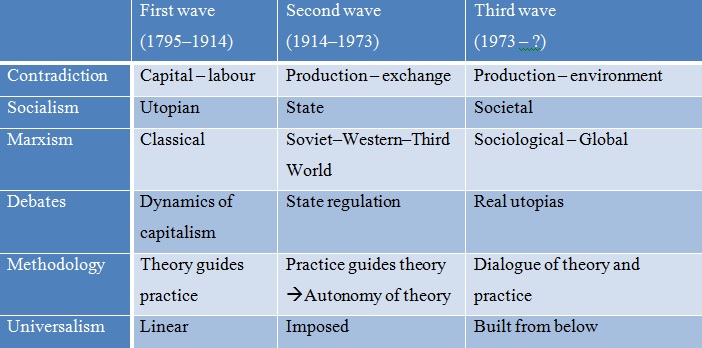

In short, each wave of marketisation is marked by successive articulations of the commodification of labour, money, and nature with corresponding countermovements of different scales and defending particular rights. Each wave differentially affects countries according to their history and placement in the world economy. Moreover, as I will now show, each wave also reflects particular contradictions of capitalism, and a particular vision of socialism as well as the defense of a particular set of rights. This movement of history gives rise to a succession of Marxisms : classical Marxism, followed by Soviet, Western and Third World Marxism, which in turn give way to what I call sociological Marxism. Let us take each in turn.

First wave : classical Marxism

In the first wave of marketisation, during the nineteenth century, the focus is on the commodification of labour – first the separation of labour from means of subsistence so that it can be bought and sold in a labour market, and then strategies by capital to reduce the cost of labour power through deskilling, employing multiple members of the family, and creating a reserve army of labour. This led to struggles that emanated from production, from factories – struggles for labour rights such as limitation of the length of the working day, protection against unemployment, the right to organise into trade unions, the extension of the vote, the development of cooperatives, and the development of political parties. The countermovement is of a local character, building toward national working class organisation to secure state enforcement of labour rights.

To this corresponds the classical Marxism of Marx and Engels and of the golden years of German social democracy, the Marxism of Kautsky, Luxemburg, and Bernstein. It is based on the idea that capitalism is a system of exploitation that is inevitably doomed because the relations of production will finally and definitively fetter the forces of production. Competition among capitalists leads to the accumulation of wealth at one pole of society and its immiseration at the other pole, which in turn gives rise to, on the one side, the deepening crises of overproduction and the recurrent destruction of the means of production and on the other side, the simultaneous intensification of class struggle. What classical Marxism shares is the view that capitalism is doomed by its own laws to destroy itself, thereby giving way to socialism.

The debate between Luxemburg (1970) and Kautsky (1971) (see also Goode, 1983) is precisely when the final crisis will occur, when the forces of production will finally be fettered or whether, as in the view of Bernstein (1961), there is no final crisis because capitalism will evolve into socialism. Despite differing views, they all shared the belief that the rise of socialism was guaranteed because capitalism was doomed. As a result socialism remained largely unexamined. It was presumed to develop on the basis of the self-destruction of the capitalist mode of production through the concentration of capital and the collectivisation of labour. In this view socialism is an economic utopia and the negation of capitalism. Classical Marxism depended on laws of history – the succession of modes of production, the dynamics of capitalism that sows the seeds of its own destruction, and history as the history of class struggle – that will inevitably lead capitalism toward socialism.

Classical Marxism suffered from three fatal flaws. First, its theory of class struggle was wrong – class struggle does not necessarily lead to its intensification but rather, through the concessions it wins, the working class becomes organised within the framework of capitalism. Second, its theory of the state was undeveloped – the state is organised to defend capitalism against capitalists as well as workers. The state recognises and enforces the material interests of workers, in a limited but crucial way, through trade unions and parties, but it also regulates relations among capitalists so that competition does not destroy capitalism. Third, and finally, its theory of socialist transition hardly existed – except in the case of Bernstein who saw it as an evolutionary process based on the inevitable expansion of electoral democracy – thereby confusing the end of competitive capitalism with the end of all capitalism, missing the way the state could contain the ravages of the market and the deepening of class struggle by creating an organised capitalism. Classical Marxists saw the signs of organised capitalism but they mistook it for socialism. In fact, organised capitalism laid the foundations of the second wave of Marxism.

Second wave : Soviet, Western and Third World Marxism

In the Polanyian account marketisation develops a new burst of energy after World War I, partly in reaction to socialist movements. But now the extent of marketisation involves not just labour but international trade and its regulation by currencies tied to the gold standard. The ever-fluctuating exchange rates that were associated with rampant inflation in Germany and the great crash in the United States led countries to protect their national currencies, and go off the gold standard. Thus, the countermovement now took the form of national regulation of economies. In Germany and Italy it took the form of fascism, in Scandinavia social democracy, and in the US the New Deal. After the civil war and with the declaration of the New Economic Policy, the Soviet Union was also taken up with marketisation, but would abandon such policies in 1928 with the inauguration of forced collectivisation in agriculture and central planning. Markets entered a period of retreat across the world and under the influence of Keynesian economics the state assumed regulatory functions. This continued until the middle 1970s when a new round of marketisation began to assert itself.

If the countermovement to the market in the nineteenth century emerged on the ground of local struggles, reflecting the coincidence of exploitation and commodification of labour, and the need to advance labour rights, the countermovement to the commodification of money – the source of second-wave marketisation – came from policies of national protection. The commodification of money, concretised in the uncertainty of currency exchange rates, created such economic chaos that national economies withdrew from the international economy. They developed coordinated policies to regulate banking but also to advance the social rights of labour through welfare states that supported those who could not gain access to the labour market through the provision of benefits for childhood, sickness, old age, job loss and so forth. Whether it be fascism, Stalinism or social democracy, social rights for labour underpinned support for the new regime. Thus, second-wave marketisation gave rise to national protection of both capital and labour, and the regulation of the commodification of money.

If the first wave of Marxism is characterised by the contradiction between capital and labour, the second is typified by the clash of the realm of production and the realm of exchange – overproduction under capitalism which called for state administration, and shortage under state socialism which called for the creation of markets (see, for example, Baran 1957 ; Sweezy 1946). [5] Far from being a utopian construct as in the first period, the notion of socialism in the second period was all too real – based on national economic planning and the protection of social rights.

Marxism, rather than projecting an imaginary socialism that would follow a hypothetical collapse of capitalism, now had to rationalise and legitimate an actually existing socialism. Marxism becomes an ideology that justifies a new form of class domination, the class domination of a party elite, sometimes referred to as the nomenklatura. The impending communist transformation and the critique of capitalism became the rallying cry of communist parties all over the world. This Soviet Marxism lost all semblance of a dynamic science, and instead became a dogma ; a degenerate branch of Marxism.

It gave rise to a reaction within the Marxist camp – what is known as Western Marxism – that simultaneously contested the Soviet Union’s claim to socialism and grappled with the failure of revolution in the West, that is, why the working class was absorbed into capitalism rather than overthrowing capitalism. Here we find, on the one hand, the writings of Georg Lukács and the Frankfurt School which underline capitalism’s powers of mystification, and, on the other side, Antonio Gramsci who explores the way advanced capitalism, and the civil society that accompanies it, organised the consent of the working class through the expansion of social rights, including certain labour rights (see for example, Gramsci 1971 ; Horkheimer and Adorno 1972 ; Lukács 1971 ; Marcuse 1955, 1958, 1964). Western Marxism, together with the social movements of the 1960s and 1970s, inspired a regeneration of Marxism that examined the question of capitalism’s durability and flexibility in the face of the crises and struggles it produced. [6]

Third World Marxism is the third tributary of second-wave Marxism – pointing to the way imperialism creates underdevelopment, calling for insulation from world capitalism and again proposing autarchic forms of state socialism. Leaving China aside, Cuba expresses this form of Third World Marxism, while dependency school theoreticians, such as Andre Gunder Frank (1966) and Samir Amin (1974), wrote from this standpoint. In the African context, Frantz Fanon (1967) is a towering figure. Taking dependency as his point of departure, Fanon analyses the balance of class forces within the anti-colonial struggle. Fearing the ascendancy of a ‘native bourgeoisie’, parasitic on international capitalism, pursuing its own power, compensating for its insecurity with conspicuous consumption, Fanon considers the possibility of a national liberation struggle forged out of the melding of dissident intellectuals and a revolutionary peasantry. Such a struggle for a participatory democratic socialism, averred Fanon, was the only hope for Africa.

Apartheid South Africa generated its own rich and distinctive second-wave Marxism that sat at the crossroads of Soviet Marxism, Western Marxism, and Third World Marxism. On the one hand, the South African Communist Party was in thrall to the Comuunist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) and followed its twists and turns, even while responding to local conditions, developing the notion of internal colonialism and ‘colonialism of a special type’. Thus, Jack and Ray Simons (1969) wrote the first great Marxist history of South Africa, showing how class and race intertwined in the formation of the South African working class. Harold Wolpe (1972) inaugurated a very different tradition of Marxist analysis, drawing on French structuralism of the 1970s to problematise the very concept of race by rooting it in the articulation of pre-capitalist and capitalist modes of production. This led to a new Marxist historiography, associated with such figures as Colin Bundy, Martin Legassick, Duncan Innes, David Kaplan, Rob Davies, Dan O’Meara and Mike Morris, that focused on the distinctiveness of the apartheid state and its relation to the capitalist class. At the same time others, such as Charles van Onselen in the tradition of E.P. Thompson, and Edward Webster in the tradition of Harry Braverman, produced highly original work on the formation of the working class by entering into its communities and its work processes. This second-wave Marxism tradition lapsed in the new South Africa, giving way to a third-wave Marxism, aimed at a critique of the post-apartheid order, and embracing the social movements that have given it expression. The essays in this book exemplify this latest wave of Marxism.

Third wave : sociological Marxism

Second-wave Marxism was concerned with building socialism on earth via a state regulated economy that ranged from social democracy to the Soviet model of planning, forms of African socialism and the Yugoslav self-managed economy. When markets were not rejected they were seen as an adjunct to the socialist project. Thus, Johanna Bockman (2011) has argued that the early thrust of neoclassical economics was to enjoin markets to a socialist project, whether this was the use of markets to help solve pricing problems of state planning or the organisation of self-management economies. The harnessing of neoclassical economics to capitalism is a more recent phenomenon distinctive to third-wave marketisation, posing once again the question of the meaning of socialism.

If classical Marxism postulated the self-destruction of the capitalist mode of production, projecting an unexamined utopian communism to follow, and if Soviet Marxism acted as a state ideology to represent an actually existing state socialism, the third wave of Marxism focuses not on the economy or the state but on civil society. Here we build on the second-wave Marxism of Gramsci who was the first to centre the importance of civil society as an institutional space distinct from, though connected to, state and economy. Just as Lenin’s writings straddled first- and second-wave Marxism, so we can say the same is true of Antonio Gramsci and hence his enduring importance. Many of Gramsci’s formulations, being in opposition to Soviet Marxism, prefigure the society-centred third-wave Marxism. Gramsci’s concern with the relation of state and civil society is, however, too limiting ; we need to add Polanyi’s concern with the relation of market and society. [7]

In contrast to Gramsci, Polanyi and Fanon, third-wave Marxism thinks of civil society in global as well as national terms – a civil society that defends humanity against mounting ecological disasters that in the final analysis assume a global scale. The commodification of nature, whether this takes the form of privatisation of water, of land or of air, generates crises that affect the entire planet. To be sure, in the short run some will be better equipped to survive disasters of earthquakes, hurricanes and floods than others but in the end we will all suffer – the prototype is disasters such as Chernobyl or the impending catastrophe of climate change. These will call for global solutions based on human rights that protect the foundations of human existence, which in turn require shutting down the capitalist mode of production that systematically destroys the environment in pursuit of profit.

In the third wave of marketisation the commodification of nature may represent the new threat to humanity, but it coexists with a recommodification of labour, as we see everywhere in the development of informalisation, flexploitation, and precarity, and with new forms of commodifying money, as we saw in the financial crisis of the 1990s culminating in the financial crisis of 2008. Bailing out finance capital has not altered the tendency to commodification of money but further consolidated it.

The collapse of state socialism in East and central Europe in 1989 and of the Soviet Union in 1991 was, in part, the result of third-wave marketisation, but it also strengthened third-wave marketisation, giving it new energy and discrediting any alternative to market supremacy. As seen from within the Soviet orbit, the illusory potentialities of a market economy were inflated by the fragility and contradictions of state socialism. Always seeking to catch up with capitalism, its incapacity to sustain a dynamic economy led to its downfall. However, during its existence the Soviet order did generate alternative visions of a democratic socialism constituted from below – the cooperatives of Hungary, the Solidarity movement in Poland and burgeoning civil society in Soviet perestroika. This socialism from below rested on the idea of the collective self-organisation of society.

Socialism of third-wave marketisation will not emerge through some catastrophic break with the past as was the case with classical Marxism nor through state-sponsored socialism from above, but through the molecular transformation of civil society, the building of what Erik Wright (2010) calls real utopias – small scale visions of alternatives such as cooperatives, participatory budgeting and universal income grants that challenge on the one hand, market tyranny and on the other, state regulation. The role of such a sociological Marxism is to elaborate the concrete utopias found in embryonic forms throughout the world. The analysis focuses on their conditions of existence, their internal contradictions, and thus their potential dissemination. Sociological Marxism, therefore, keeps alive the idea of an alternative to capitalism, an alternative that does not abolish markets or states but subjugates them to the collective self-organisation of society.

Table 2 : Three waves of Marxism

The methodology employed by each wave of Marxism involves different relations between theory and practice. For classical Marxism theory dictated to practice : theory determined the inevitable collapse of capitalism and rise of socialism, so practice was only affected by knowing where one was in the historical trajectory. For Soviet Marxism practice – national survival at all costs – dictated to theory. Marxism was a thinly disguised ideology of the ruling party state. Sociological Marxism abandons theoretical certainties and practical imperatives and seeks instead to achieve a balance or dialogue of theory and practice. The point is not only to change the world now that we have understood it, but also to change it in order to understand it better. We search out real utopias that can galvanise the collective imagination but also interrogate them for their potential generalisability (see Burawoy and Wright 2002).

If classical Marxism offered a universality based on flawed laws of history, and Soviet Marxism offered a universality based on a singular dictatorial regime, sociological Marxism offers us no guarantees, only an eternal search and reconstruction, a universality that is always contingent, created from the concrete with the help of the abstract (see Hall 1986).

Toward a Global Marxism

To some, sociological Marxism is an oxymoron – after all, classical Marxism dismissed sociology as bourgeois ideology, and if Western Marxism borrowed from sociology, especially from Weber and Freud, it was not to elevate the idea of civil society. Gramsci himself was dismissive of sociology as concerned only with the spontaneous and thus the trivial. [8]

Why now sociological Marxism ? Simply put, sociology’s credentials as critic of marketisation and statisation are unquestioned. Whether we turn to the writings of Weber or Durkheim, Simmel or Michels, Elias or Parsons, Habermas or Bourdieu, the critique of economic reductionism and instrumental rationality is central. Perhaps the state might have been seen as a potential or partial neutraliser but today that possibility seems to have evaporated. As the state seems to be ever more in thrall to the market, the defense of an independent ‘civil society’ seems to become all the more necessary. The problem, however, with sociology – and we might say the same of Gramsci and Polanyi – is that the notion of ‘civil society’ was contained within national boundaries. Today, we have to give the idea a transnational scope.

Marketisation – the commodification of labour, money and nature – is affecting all parts of the planet. No one escapes the tsunami, although some are able to mount more effective dykes. On the face of it, there needs to be a global solution but here we should proceed carefully as solutions can turn out to be as bad as the problem they seek to fix. What could be worse than a planetary totalitarianism, constituted in the name of preventing destruction of the environment. We might be better off knitting together national solutions that centre on society. However, here again we see problems as the state of societies is very different : in South Africa it is fissiparous, in China it is precarious, in Russia it is gelatinous. In every country we need to reconnoitre the trenches of civil society, map out the relations between society and state, society and market. Only in that way can we better understand the possibilities for global connections. Only in that way can we better understand the possibilities for real utopias.

As we think about a global civil society, we must also think of a global Marxism, that is, a Marxism that transcends but also recognises national and regional configurations. If first-wave Marxism was national in scope, and second-wave Marxism was regional (Soviet, Western and Third World), today we have the possibility of a Marxism that still recognises nation and region but also encompasses pressing experiences shared across the world, albeit unevenly. And if first-wave Marxism projected socialism as a utopia guaranteed by laws of history, and if second-wave Marxism became a ruling ideology, justifying socialism as Stalinism – utopia-become-dystopia – then third-wave Marxism constructs socialism piecemeal as an archipelago of real utopias that stretch across the world, attracting to themselves populations made ever more precarious by third-wave marketisation. The Marxist becomes an archeologist digging up alternatives spawned and wrecked by the storms of capitalism and state socialism.

{{}}Finally, and most ominously, we face the creation of another fictitious commodity, one that Polanyi never anticipated – knowledge. We live in a world where knowledge is ever more important as a factor of production, whose production and dissemination is ever more commodified. The university, once a taken-for-granted public good has become a private good subject to the dictates of the market. Students become fee-paying consumers in search of vocational credentials that guarantee them little but lifetime debt, faculties are diced and spliced into the casualised labour of teachers and researchers, non-academic staff are outsourced while administrators become highly paid managers and corporate executives. The university that cultivated citizens for a democratic polity and produced knowledge to solve societal problems, is being transformed into an instrument of the short-term demands of capital at the very time its contributions to the survival of the planet are most needed. The struggle for the university becomes a struggle not just for its own survival ; it has a central role to play in any countermovement to third-wave marketisation, a possible Modern Prince for the defense of modern society.

References

Althusser, L. 1969. For Marx. London : Allen and Unwin.

Althusser, L. 1971. Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays. London : New Left Books.

Amin, S. 1974. Accumulation on a World Scale. New York : Monthly Review Press.

Anderson, P. 1976. Considerations on Western Marxism. London : New Left Books.

Baran, P. 1957. The Political Economy of Growth. New York : Monthly Review Press.

Bernstein, E. 1961. Evolutionary Socialism. New York : Schocken Books.

Bockman, J. 2011. Markets in the Name of Socialism. Stanford : Stanford University Press.

Burawoy, M. 2003. ‘For a sociological Marxism : the complementary convergence of Antonio Gramsci and Karl Polanyi’, Politics and Society, 31 (2) : 193–261.

Burawoy, M. and Wright, E.O. 2002. ‘Sociological Marxism’. In Handbook of Sociological Theory, edited by J. Turner. New York : Plenum Publishers.

Fanon, F. 1967. The Wretched of the Earth. Harmondsworth, UK : Penguin Books.

Goode, Patrick (editor). 1983. Karl Kautsky : Selected Political Writings. London : MacMillan.

Gramsci, A. 1971. Selections from Prison Notebooks. New York : International Publishers.

Frank, A.G. 1966. Development of Underdevelopment. New York : Monthly Review Press.

Hall, S. 1986. ‘The problem of ideology- Marxism without guarantees’., Journal of Communication Inquiry, 10 (2) : 28–44.

Harvey, D. 2003. The New Imperialism. New York : Oxford.

Harvey, D. 2005. A Short History of Neoliberalism. New York : Oxford

Horkheimer, M.and Adorno, T. 1972. Dialectic of Enlightenment. New York : Seabury Press.

Kautsky, K. 1971. The Class Struggle. New York : Norton.

Klein, N. 2007. The Shock Doctrine. New York : Henry Holt & Co.

Kolakowski, L. 1978. Main Currents of Marxism (three volumes). Oxford : Oxford University Press.

Kornai, J. 1992. The Socialist System. Princeton : Princeton University Press.

Lenin, V. 1963. ‘Imperialism : the highest stage of capitalism’. In Volume 1 : Selected Works. New York : Progress Publishers.

Lichteim, G. 1961. Marxism. London : Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Lukács, G. 1971. History and Class Consciousness. Cambridge, MA : MIT Press.

Luxemburg, R. 1970. ‘The mass strike, the political party and the trade unions’ ; ‘Reform or revolution’. In Rosa Luxemburg Speaks. New York : Pathfinder Press.

Marcuse, H. 1955. Eros and Civilization. Boston : Beacon Press.

Marcuse, H. 1958. Soviet Marxism. New York : Columbia University Press.

. 1964. One Dimensional Man. Boston : Beacon Press.

Marx, K. 1967. Capital (three volumes). New York : International Publishers.

Mandel, E. 1975. Late Capitalism. London : New Left Books.

Miliband, R. 1969. The State in Capitalist Society. New York : Basic Books.

Nove, A. 1983. The Economics of Feasible Socialism. London : Allen and Unwin.

Parsons, T. 1967. ‘Some comments on the sociology of Karl Marx’. In T. Parsons, Sociological Theory and Modern Society. New York : Free Press.

Polanyi, K. 1944. The Great Transformation : The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time. Boston : Beacon Press.

Poulantzas, N. 1973. Political Power and Social Classes. London : New Left Books.

Simons, R. and Simons, J. 1969. Class and Colour in South Africa, 1850–1950. Harmondsworth, UK : Penguin Books.

Sweezy, P. 1946. The Theory of Capitalist Development. New York : D. Donson.

Thompson, E. P. 1963. The Making of the English Working Class. London : Victor Gollancz.

Williams, W.A. 1961. The Contours of American History. Cleveland : World Publishing Co.

Wolpe, H. 1972. ‘Capitalism and cheap labor power in South Africa : from segregation to apartheid’, Economy and Society 1 : 42–456.

Wright, E.O. 2010. Envisioning Real Utopias. London : Verso.